“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” -- George Santayana

According to historians, the first mention of

learning disorders was recorded in what is known as "The Therapeutic

Papyrus of Thebes" dating roughly to 1550 BC. Both Greek and Roman

mythology are rampant with stories and imagery of infanticide;

this does not appear to be by accident. Children deemed unfit or

unwanted in ancient Rome (including girls) were 'discarded' in sewers or

left to the elements to die (be "exposed"). Often a cord would be tied

to their feet to alert anyone that may find them of their unworthiness

and discourage them from being adopted. They were also frequently

thrown in the Tiber river and if left alive, were certainly the objects

of much derision and were often sold into slavery. Those with

intellectual disabilities in particular were referred to as 'idiots'. Plato (427-347 B.C.) in The Republic promoted selective breeding (of humans) and infanticide:

Claudius Galen (138-201), often called the father of Neurology, described the brain as "the seat" of intellectual functioning. On the subject of intellectual disability:

Seven edicts were issued from Rome between 315 and

451. Included in these were the Councils of Vaison (442), Aris (452)

and Agde (505) which stated that unwanted children should be abandoned

in a church and granted sanctuary within for 10 days. Special marble

basins were placed at church doors to receive the newborn infants.

Abandoning them to the elements was now considered to be homicide. The

Council of Nice (325) stated that each (Christian) village should create

a hostel for the sick, poor and homeless (a xenodochium). Later, many of these would convert to a brefotropio

or an asylum for orphaned children. The Archbishop of Milan, Datheus,

has been credited with creating the first asylum for abandoned children

in 787. A revolving receptacle delivered the infant anonymously to the

asylum; a bell was rung to announce the child's arrival.

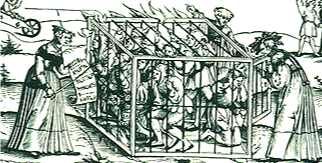

After the Crusades

(1101-1272), the incidence of leprosy began to decrease and former

leper colonies were converted to house what society considered to be

'deviant'. Included in these "Cities of the Damned" were the physically

disabled and the mentally delayed as well as those with incurable

diseases, the homeless, the mentally ill, orphans, criminals,

prostitutes and widows. 'Idiot cages' were often erected in town squares

to contain those less fortunate to 'keep them out of trouble'. It is

possible that these provided entertainment for the townspeople. Often,

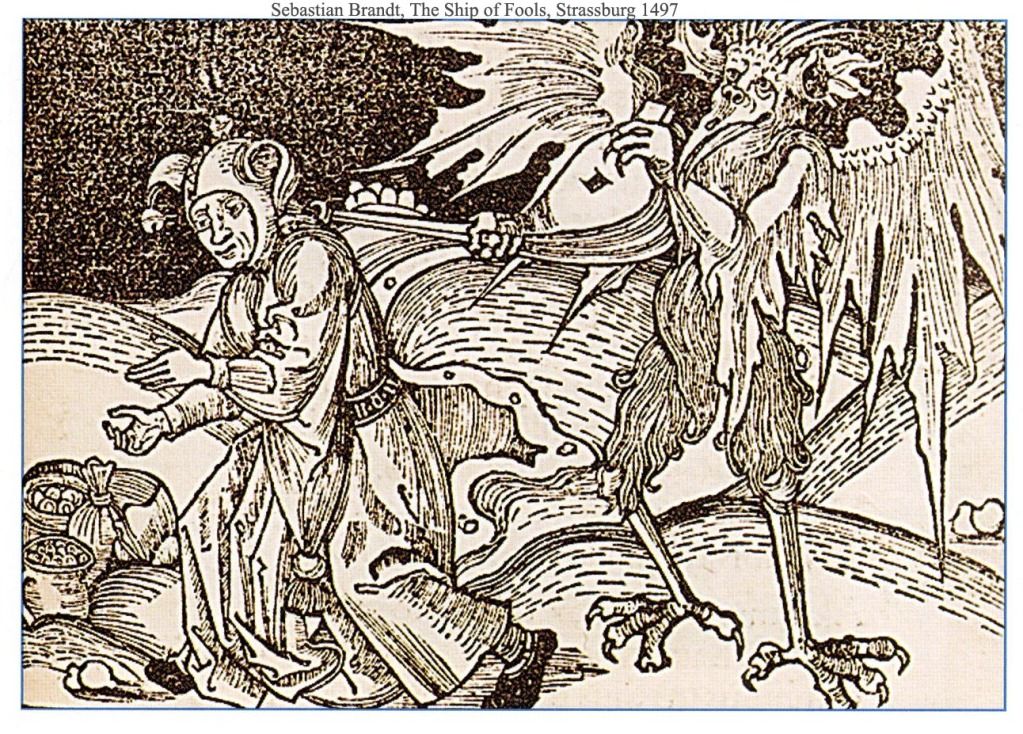

sailors were paid to take those deemed to be a burden away; this begat

the 'ship of fools' where 'undesirables', such as the learning disabled,

were sailed from port to port to provide entertainment for the

locals. The ships were later abandoned and the people left to fend for

themselves and ultimately, perish.

It is around this time that Maimonides (1135-1204), the Jewish philosopher and physician, wrote that problems of learning and memory were produced by the phlegmatic brain due to the presence of too much humidity. Maimonides proscribed to an idea originally devised by Hippocrates (460-370 BC), that the body was controlled by four humors and personality, temperament, intelligence and overall health was determined by their balance. This theory would continue to flourish for several centuries to come.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) credited as being one of the fathers of Christian reformation, openly called for the killing of the mentally disabled for he felt that they were possessed by the devil:

The first distinction between the mentally ill and the intellectually disabled was made by Paracelsus (1493-1541), a Swiss physician and botanist. Likening them both to animals and acknowledging that there were many different 'kinds' of both, he stated that the feeble-minded were not unlike a healthy animal, while the psychopath was very much a sick animal. Another Swiss physician, Felix Plater (1536-1614), proposed the term 'alienation' to describe both the mentally ill and the developmentally delayed. As a result, psychiatrists were referred to as 'alienists' for the next few centuries. Unlike many of his peers before and after him, he explored the life of his charges by actually living and experiencing the cells, cages and conditions that his patients did. Truly a compassionate man for the times, he declared that the dungeon-like conditions that his patients lived in should not be permitted in society. On the subject of the developmentally delayed;

Although the Catholic church continued to found

hospitals, homes for the blind and orphanages, most physically and

mentally disabled persons eked out meager existences by begging. Queen Elizabeth I of England ensured that several laws were passed during 1563 and 1601 to aid the disadvantaged. Known as the 'Elizabethan Poor Laws' they ensured the creation of Almshouses for the aged poor, Workhouses

for the employable poor and basic care was provided for the

'unemployable poor'. Regardless, the conditions in these facilities was

abysmal. Two French facilities were created decades later: in 1657, the

Salpêtrière (containing 1,416 women and children) and the Bicêtre (which contained 1,615 men).

In 1751, a hospital in Philadelphia created a

separate section for people with developmental delays and mental

illness. This unit was moved to the cellar by 1756 and much like other

hospitals of it's day, including Bedlam, put the inmates on display for a

small fee. In fact, many of the cells had street level windows and it

was quite a past-time to watch the 'antics' of the patients.

One of the more notable among these new advocates was

an American Sunday School teacher named Dorothea Dix. After touring

the country and observing the deplorable conditions and treatment of the

disenfranchised in America, most notably the mentally delayed and the

mentally ill, Dorothea was driven to make changes. As she was a woman

and therefore at the time, ineligible to speak in front of the US

congress, she had a well known male social reformer, physician and

founder of the Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Youth, Samuel Gridley Howe,

to deliver her speech in 1854. From her observations, we can

understand in a very clear manner the treatment that many patients

experienced;

"Thesselonians 1:5." Holy Bible, King James Version, Cambridge Edition. Online Parallel Bible. Web. http://bible.cc/.

[Originally appeared on Down Wit Dat]

Where We Have Been: The Roots of Institutionalization and Eugenics

In past installments of A Brief History of Down syndrome, we have explored the origins of the name, examples of Down syndrome in art (dating back to prehistory) and looked at famous families with a member with Trisomy 21.

In this entry, I aim to show the history of the learning disabled

including societal roles and treatment. Many people have a vague

understanding that up until recently, people were institutionalized

indefinitely for having mental illnesses and developmental delays. Some

may also be aware of the atrocities performed on those with disabilities

before and during the Second World War. However, what brought society

to these extremes? Where have we been that has brought us to where we

are now? What were we thinking?

Ancient Perceptions of the Developmentally Delayed

|

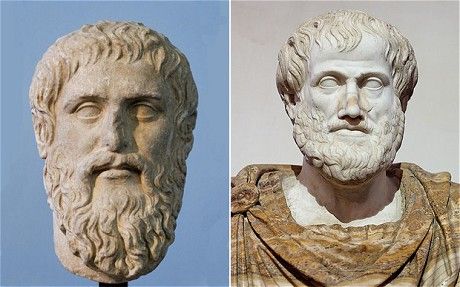

| Both Plato (L) and Aristotle (R) endorsed what would be Eugenics |

"..the best of either sex should be united with the best as often, and the inferior with the inferior, as seldom as possible; and that they should rear the offspring of the one sort of union, but not of the other, if the flock is to be maintained in first-rate condition... but the offspring of the inferior, or of the better when they chance to be deformed, will be put away in some mysterious, unknown place, as they should be."

Aristotle (384-322BC), stated in Politics: "As to the exposure and rearing of children, let there be a law that no deformed child shall live..." Such a law is reported to have existed in Sparta, where according to legend, children deemed unfit were thrown into a chasm near Mount Taygetus.

The practice of keeping a 'fool' (a mentally challenged or physically

disabled person) as a source of entertainment also dates back to ancient

Rome. With the rise of Christianity however, the practice of

infanticide was discouraged. St. Paul (5-67AD), in particular, encouraged his followers to "...comfort the feeble minded, support the weak, be patient toward all men.".

Claudius Galen (138-201), often called the father of Neurology, described the brain as "the seat" of intellectual functioning. On the subject of intellectual disability:

"Slow thinking is due to the brain's heaviness. Its firmness and stability produce the faculty of memory. Imbecility results from the rarefaction and diminution in quality of the animal spirits and from the coldness and humidity of the brain."

|

| Visiting the revolving cradle or baby hatch. |

During

the Dark or Middle ages after the fall of Rome, there appeared to be

two approaches to the mentally delayed. Parallel to the concept of

'loathsome imperfection' existed the idea of the "Children of a caring

God" or "Les enfents du Bon Dieu" which can be found in the writings of Confucius, Zoroaster and the Koran. Although special, these 'divine idiots' were still considered abnormal and separate from the rest of society.

|

| An 'idiot cage' |

|

| A "ship of fools" |

It is around this time that Maimonides (1135-1204), the Jewish philosopher and physician, wrote that problems of learning and memory were produced by the phlegmatic brain due to the presence of too much humidity. Maimonides proscribed to an idea originally devised by Hippocrates (460-370 BC), that the body was controlled by four humors and personality, temperament, intelligence and overall health was determined by their balance. This theory would continue to flourish for several centuries to come.

Although founded in 1247 as a priory, St. Mary of Bethlehem asylum or "Bedlam"

became a hospital in 1337 and began admitting 'deviants' in 1357.

Among the inventory in 1398, it was found to have, for a total census of

twenty patients: four sets of manacles, eleven chains of irons, six

locks and keys and two stocks. In stark contrast to Bedlam however, is

the town of Geel in Belgium. During this same time, a community of

foster care was set up where the townspeople opened their doors to the

mentally ill and delayed. It is reported that they ate, slept and

worked like members of the family. Similar programs would not exist

world wide until hundreds of years later. These practices have

continued in Geel until the present day. What was then a small village

is now a hub of mental health and related services in present day

Europe.

| |

| Woodcutting from the 1497 play Das Narrenschiff or "Ship of Fools" |

Martin Luther (1483-1546) credited as being one of the fathers of Christian reformation, openly called for the killing of the mentally disabled for he felt that they were possessed by the devil:

"Eight years ago, there was one at Dessau whom I, Martinus Luther, saw and grappled with. He was twelve years old, had the use of his eyes and all his senses, so that one might think that he was a normal child … So I said to the Prince of Anhalt: "If I were the Prince, I should take this child to the Moldau River which flows near Dessau and drown him..."

"...Was firmly of the opinion that such changelings were a mass of flesh with no soul. For it is in the Devil‟s power that he corrupts people who have reason and souls when he possesses them. The devil sits in such changelings where their soul should have been!"

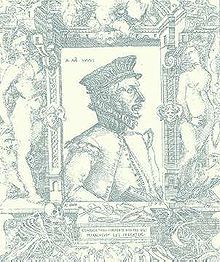

|

| Felix Plater |

The first distinction between the mentally ill and the intellectually disabled was made by Paracelsus (1493-1541), a Swiss physician and botanist. Likening them both to animals and acknowledging that there were many different 'kinds' of both, he stated that the feeble-minded were not unlike a healthy animal, while the psychopath was very much a sick animal. Another Swiss physician, Felix Plater (1536-1614), proposed the term 'alienation' to describe both the mentally ill and the developmentally delayed. As a result, psychiatrists were referred to as 'alienists' for the next few centuries. Unlike many of his peers before and after him, he explored the life of his charges by actually living and experiencing the cells, cages and conditions that his patients did. Truly a compassionate man for the times, he declared that the dungeon-like conditions that his patients lived in should not be permitted in society. On the subject of the developmentally delayed;

"Now we see many (foolish or simple from the beginning) who even in infancy showed signs of simplicity in their movements and laughter, who did not pay attention easily, or who were docile and yet they do not learn. If anyone asks them to do any kind of task, they laugh and joke, they cajole, and they make mischief. They take great delight and seem satisfied in the habit of these simple actions, and so they are taught in their homes..."

"We have known others who are less foolish, who correctly attend to many tasks of life, who are able to perform certain skills, yet they show their dullness, in that they long to be praised and at the same time they say and do foolish things..."

"Some people have dullness from before birth. Such persons have deformed heads, or they spoke with a large tongue and at the same time with a humorous throat, or they were deformed in their general appearance."

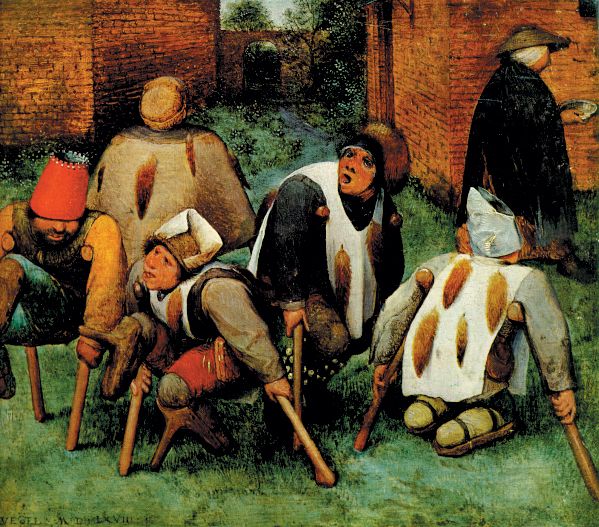

|

| The Beggars by Pieter Bruegel (1568). |

Philip Pinel

(1745-1826), the French 'Alienist', believed that those labelled

'mentally deranged' suffered from a disease process instead of simply

having sinful or immoral natures. He removed the restraints and chains

from the Bicêtre and the Salpêtrière and instead employed more gentle

methods on the inhabitants there (who were now referred to as

'patients').

Despite these inroads in both the scientific world and societal compassion, the stigma against the less fortunate and different continued. Rev. Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) published "Essay on the Principle of Polulation..." in 1798 which openly criticized the Poor Laws. His proposed methods included curbing the birth rate and the elimination of undesirable traits, which he surmised, could not occur without "condemning all the bad specimens to celibacy...".

Despite these inroads in both the scientific world and societal compassion, the stigma against the less fortunate and different continued. Rev. Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) published "Essay on the Principle of Polulation..." in 1798 which openly criticized the Poor Laws. His proposed methods included curbing the birth rate and the elimination of undesirable traits, which he surmised, could not occur without "condemning all the bad specimens to celibacy...".

With

the rise of the industrial revolution, people emigrated en masse to

urban areas in the hopes of finding work. Factories often employed poor

children cheaply; factory owners were pressured by the local parish

authorities to take one "imbecile" for every twenty typical children.

In this time, the deviant and undesirable were subjected to "warning

out" and "passing on" where they were loaded in a cart and dropped off

at the next town.

|

| Bedlam, William Hogarth, 1735 |

Another physician (and student of Pinel) Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol (1782-1840)

revolutionized the idea of intellectual disability by dividing it into

two categories. The first category, known as 'imbeciles' were described

as:

"... Generally well-formed, and their organization is nearly normal. They enjoy the use of the intellectual and affective faculties, but in a less degree than the perfect man, and they can be developed only in a certain extent. Whatever education they may receive, imbeciles never reach the degree of reason, nor the extent and solidity of knowledge, to which their age, education and social relations, would otherwise enable them to obtain. Placed in the same circumstances as other men, they do not make a like use of their understanding..."

"...The innocence and jovial manners; the gayety and piquant repartees; the pleasant and sometimes very judicious sallies of some imbeciles; have caused them to be admitted to the presence of the great, and even that of kings, to divert them from their distressing ennui, and to afford them recreation. There is, in courts even, the post of fool."

"Imbeciles possess, therefore, sensibility, a certain degree of intelligence and a weak memory. They comprehend what is said of them, make use of speech, of if mute, express themselves by signs. They are capable of acquiring a certain amount of education, and possess moral affections: but given up to their own control, they very easily become degraded. Imperfectly nourished, and poorly protected from the effects of the weather; filthy in their habits, and giving themselves up to errors of regimen; their health becomes impaired; the little intelligence with which they were originally endowed, enfeebled; and at length, the imbecile, who is brought to a hospital, presents all the characteristics of idiocy."

"Idiocy" was defined as "the utmost limit of human degradation...".

By the mid

1800's, the increased interest in social issues and the care of the

disadvantaged was now producing some rudimentary advocacy; the learning

disabled were now seen as having some worth and were at least trainable

if not 'curable'. A reflection of this is the opening of a 'training

school' for disabled children in Berlin in 1842; another opened in

Leipzig four years later. Training schools were also opened in England

around this time. Édouard Séguin

(1812-1880), a physician and education specialist opened a private

training school for the developmentally delayed in approximately 1840.

1842 also saw the publication of Séguin's Traitement Moral, Hygiène, et Education des Idiots

(The Moral Treatment, Hygiene, and Education of Idiots and Other

Backward Children) which is considered to be the first textbook

dedicated solely to the diagnosis and treatment of the intellectually

disabled.

Roughly at this time, a young doctor named Johann Jakob Guggenbühl (1816-1863) established a school for "cretins"

in Interlaken, Switzerland. The Abendberg started with good intentions,

however it quickly fell into neglect and abuse as his traveling

schedule kept him away from his students for great lengths of time. It

was considered to be his personal failure.

|

| Dorothea Dix |

"I have myself seen more than nine thousand idiots, epileptics, and insane, in these United States, destitute of appropriate care and protection; and of this vast and most miserable company sought out in jails, in poor-houses, and in private dwellings, there have been hundreds, nay, rather thousands, bound with galling chains, bowed beneath fetters and heavy iron balls, attached to drag-chains, lacerated with ropes, scourged with rods, and terrified beneath storms of profane execrations and cruel blows; now subject to gibes, and scorn, and torturing tricks-now abandoned to the most loathsome necessities, or subject to the vilest and most outrageous violations. These are strong terms, but language fails to convey the astounding truths."

Dorothea's bill

to set aside 5 million acres across the US for the creation of

federally run, more humane facilities was passed by the US Congress, yet

promptly vetoed by then president, Franklin Pierce.

More

training schools for the "feeble minded" opened in the US between 1852

and 1858 in Germantown PA, Albany NY and Columbus OH. Following

Séguin's methods, these schools had a focus on education, physical and

sensory development, life and social skills. They were considered a

success and many families with learning disabled members turned to them

for hope. Sadly, that hope would be dashed in the years to come.

[Next time: From Education to Eugenics]

Aristotle. Politics. The Internet Classics Archive. Web Atomics. Web. <http://classics.mit.edu/index.html/>

Dix, Dorothea L. "Memorial Of Miss D. L. Dix To the Senate And House Of Representatives Of The United States." Address. In the Senate of the United States. USA. 23 Jan. 1854. Disability History Museum. NEC Foundation of America. Web. <http://www.disabilitymuseum.org/dhm/index.html>.

Esquirol, Etienne. Mental Maladies; a Treatise on Insanity. New York: Hafner Pub., 1845. Internet Archive. Web. <http://archive.org/>.

Kanner, L. A History of the Care of the Mentally Retarded. Springfield, IL, 1964.

Luther, Martin. Werke, Kritische Gesamtausgabe: Tischreden. Vol. 5. Böhlau: Weimar, 1912-1921. Print.

Malthus, Thomas Robert. An

Essay on the Principle of Population, or a View of Its Past and Present

Effects on Human Happiness; with an Inquiry into Our Prospects

Respecting the Future Removal or Mitigation of the Evils Which It

Occasions. 6th ed. 2 Vols. London: John Murray, 1826. Online Library of Liberty. Web. http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com_staticxt.

Millon, Theodore. Masters of the Mind: Exploring the Story of Mental Illness from Ancient Times to the New Millennium. John Wiley and Sons, 2004. Print.

Millon, Theodore. Masters of the Mind: Exploring the Story of Mental Illness from Ancient Times to the New Millennium. John Wiley and Sons, 2004. Print.

Paralells in Time; A History of Developmental Disabilities, The Minnesota Governor's Council on Developmental Disabilities, 2012.

Plato. The Republic, Book V., 360 B.C.E. The Internet Classics Archive. Web Atomics. Web. <http://classics.mit.edu/index.html>.

Scheerenberger, R. C. A History of Mental Retardation. Baltimore: Brookes, 1983. Print.

Scheerenberger, R. C. A History of Mental Retardation. Baltimore: Brookes, 1983. Print.

Schneider, Dona, and Susan M. Macey. "Foundlings, Asylums, Almshouses And Orphanages: Early Roots Of Child Protection." Middle States Geographer, 35 (2002): 92-100. Buffalo State Geography and Planning Department. Buffalo State University. Web. <http://www.buffalostate.edu>.

[Originally appeared on Down Wit Dat]

No comments:

Post a Comment