Nope. No actual water in this post.

What

is raising awareness? Is it asking people to realize that something exists? Is it factual information? Is it trying to wake people up to the reality around them? Or does it carry with it the connotation that there is something one should be aware of so that it doesn't sneak up on one, so that one is not, let's say,

affected by a

condition?

Lately, I've been having an increasingly difficult time with seeing raising awareness as something that results in a purely positive outcome. It is no longer enough for me to say that we need to move on from awareness, that awareness is fine and all, but that

we need to do more. Now I have to go and question the whole idea of 'raising awareness' too. But then again, that's what I do: I can't just, for the sake of Frank and all of his penguin minions, accept things for what they are - good and pure and nice and not meant like

that. </sarcasmfont>

I always have to dig, wonder, question, and reflect.

Dammit, if I'm not just "full of hate" and "looking for things to be confrontational about." Ho hum. Yes, more sarcasm.

But October is

Down Syndrome Awareness month. There will be many people who will be especially vocal about Down syndrome, many bloggers who will be doing a blogging prompt called 31 for 21, which essentially means that they'll be writing a post to

raise awareness about Down syndrome every day of the month of October. I wish I had that kind of blogging energy or the inspiration, but there just isn't enough coffee or wine in this world for me to blog every day (also, there may be too much good stuff to read to actually produce any stuff of my own). I own that.

Last year I managed one post. This year I'm not even going to preface this post with a bunch of excuses. You all know I spend a lot of time just

sitting chasing a wily toddler drinking thinking not cooking reading doing laundry resetting and degooifying the 'puter, the iPad, my phone, and the DVR living and being generally a big wet blanket, right?

I'm excused and can just harp from the sidelines. Awesome.

There will be many, many posts about Down syndrome. Countless cute, some not so cute, and maybe a few 'educational' photos. Lots of talk and stories, and the like. Plenty of dispelling of false or antiquated beliefs and completely wrong information. Some complaints. Many funny anecdotes and observations. Some facts, many should-be-but-maybe-not-exactly-are-facts, and perhaps a few beliefs and observations masquerading as facts. Still, lots of good, lots of community, and lots of love.

Love is always nice. Isn't it just?

But sometimes

we I have to be contrary. Sometimes I have to embrace

my anger at the society as a valuable tool, turn it into outrage, and challenge the very things I apparently should not be questioning. Because if things make us feel good, help us get by, or help to keep the boat from rocking, if they make us feel like "we're all in this together," they are beyond reproach. Huh? And questioning ideas written in stone as far as Down syndrome goes would just be mean and divisive and not beneficial to

the cause.

It could fuck with the kumbaya.

Yeah. There'll be things in this month of blogging I want no part of. Because raising awareness - especially when this 'raising awareness' opens the door to pretty much anything one wishes to say about whatever that awareness is being raised about - does not necessarily promote meaningful inclusion, acceptance, or equal rights. Which, incidentally are

the cause I'm interested in.

Awareness does not necessarily lead to acceptance. Ideally it does, but ideally I'd also be blogging every day this month to a receptive audience, and always have the sun shine when I need to get across the Target parking lot with a toddler and a couple dozen pounds of Halloween candy. And ideally I'd have no desire to eat said candy. Ideally my kid would just stick with saying the "no" when she doesn't want to eat something and skip the grand display of 'here, this is how much I will not eat this crap and will instead place it in your lap, on the chair, and on the floor'. Ideally.

But that's just not how stuff shakes out. Or doesn't. Egg stains, people. Egg stains.

Sometimes raising awareness about Down syndrome becomes about a heightened sensitivity to that which all too easily makes a person with Ds

the Other, and worse yet, people with Ds a unified, homogeneous

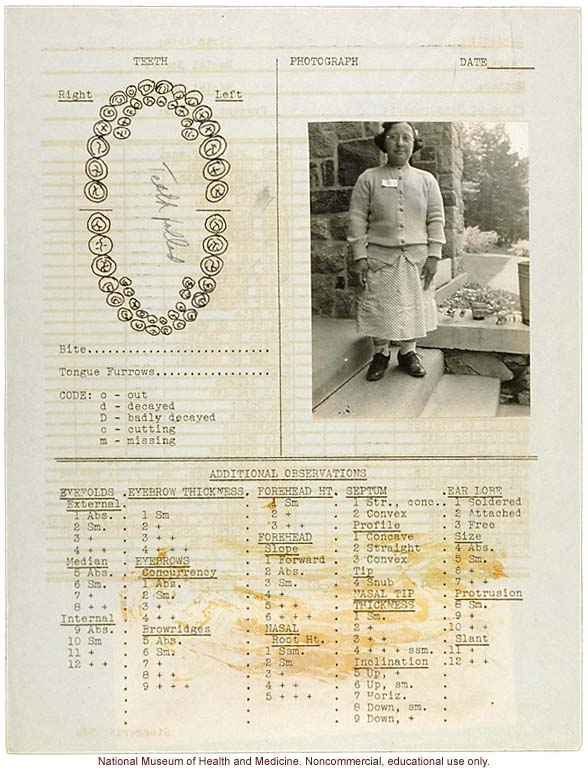

group Other. Awareness of a condition can lead to the idea that people with the condition need to be

handled or

dealt with in a certain way, differently from those without the condition, and potentially to the notion of differing expectations

of the people with the condition. Raising awareness about Down syndrome,

the genetic condition, can easily

chip away at the individuality of a person with Down syndrome,

the people who have this genetic condition, by drawing on generalizations and sometimes even stereotypes, and by linking the condition with a person's identity to such an extent that the person's other identities will always take the backseat, if the observer is even willing to entertain identities beyond 'a Down syndrome person' to begin with. In reality, any awareness about Down syndrome focusing on anything specific (I use this word while understanding that there is nothing purely specific to Trisomy 21) regarding Down syndrome will naturally work to Other people with Down syndrome for the unaffected observer. Awareness can erode individual personhood by zeroing in on perceived commonalities and differences from the 'general populace' in a way that

directly and simply links them to that triplicate of the 21st, instead of making all of the necessary connections, such as the connections to and considerations of intellectual ability, gender, upbringing, nationality, daily routine, age, height, placement in the order of siblings, religion, genetic makeup, ethnicity, social circles, hair color, education, physical ability, disposition, and countless,

countless, other outside factors. I say 'outside', because the importance we attach to any of these factors, including one's chromosome count, comes from the 'outside', the social constructs at work in our environment.

My child does not enjoy music because she has Down syndrome. She enjoys music because she has existed since before her birth constantly listening to it, because I enjoy music, because she's been enrolled in music classes since she was 6 months old, because I sing to her, because her father sings to her, because her grandparents sing to her, because if I run out of avenues to entertain her I put on Baby Signing Time - the ones with all of the songs, because she sees that music makes the people around her happy and content and it's part of the celebration in our lives. Yes, the love of music is in her genes too, but she doesn't enjoy it because she has a third copy of the 21st chromosome.

Notice the difference?

Awareness can all too easily become about "Down syndrome things." It can slip from medical conditions

slightly more prevalent in the population with Ds to complex behavioral patterns directly linked to the chromosome, insidiously enforcing Othering and, in the worst case scenario, allowing for medical professionals, far too quickly, to brush off valid medical issues that need attending to with "We often see this in Down syndrome," and simply resort to awareness instead of taking action (See what I'm doing here, making too simplistic a connection, a connection that kind of sounds like it fits and in a way it does, but when you really think about it hides behind it a much more intricate process?)

Granted, this looking at perceived commonalities can make us parents of individuals with Ds feel safe and secure in shared experience, but is it really worth it? Do I need 'support' and 'community' more than I need for the world to accept my child as is, without a laundry list of 'Associated with Down Syndrome'? Do I crave similarity and things made simple more than I do the adventure and acceptance of the unknown that is the individual life I lead? In reality, Down syndrome is not even a syndrome. It's a genetic variant called Trisomy 21, not a group of

co-occurring symptoms. The

symptoms of Down syndrome are after all such horrifying inflictions as a single palmar crease, epicanthic folds, impaired intellect, and other life-threatening abnormalities, none of which are present,

ever, in the general population, but are always,

always present in Down syndrome. There really should be a pill, you know.

Excuse me while I scream in frustration. Having to be

that facetious and liberal with italics does that to a person, you know.

(There would be a really cool gif right here of someone notorious screaming, right after rolling their eyes, if I were able to create one. Or understood what gifs are, really. Next century, I swear.)

I like a nice community feeling, of course I do. Do I believe that having Down syndrome should naturally lead to membership in a community, a tribe? Is there anything so specific about Down syndrome that my child needs to have others in her life who also have Down syndrome, have a doll that has Down syndrome, or have her parents associate with other parents of children with Down syndrome? No. I do believe that there may come a time that my child will enjoy having friends who also have an intellectual disability, and/or will have a hard time keeping friends who do not have an intellectual disability, yes, but that doesn't have anything to do with Down syndrome specifically. There may also come a time that she will not want to play with some kids because they're not into playing 'zoo' or building with legos, and there might come a time she won't want to hang out with someone because all they speak about is the crappy music of the latest Justin Bieber, and, well, there's just more to life than tween pop.

I'll let her find her own way.

Ideally, I'd like to have her find it without having a certain type of

awareness hanging over her head while she's trying to go up and talk to a kid, sign 'play', and then rip a ball right out of that kid's hands like that's what it means to share (true story, y'all). In the future, she might not always fit in because of how our society treats people with intellectual disabilities, but because of her Down syndrome? Only if we let it become synonymous with her identity.

Ideally, I'd like to be a part of a larger disability community as an ally. A community which unites because of how the 'able' population in society view and treat their disabled fellow humans, not because I'm interested in romanticizing the extra chromosome in my daughter's cells. A community that doesn't commiserate and isn't heavy handed with honey (and fundraising) when in fact vinegar is called for.

So while I celebrate my child in this month of October, it being her birthday month and all, and in all the other months, and while I have no problem whatsoever with Down syndrome in general, and my kid's Down syndrome which I wouldn't wish away in a million years, specifically, I wish we were part of a community that comes together as a resistance formed because of the segregation and oppression of those with Down syndrome, not a community that unwittingly sometimes contributes to the Othering of my child and

others like her (See what I did there? That's how easily we slip and begin sliding...).

Anyhoo, who's in for a little overthrowing? I'm free most Saturdays and come with wine.

This post appeared originally on 21+21+21=?